- Joined

- Feb 19, 2010

- Messages

- 489

- Points

- 168

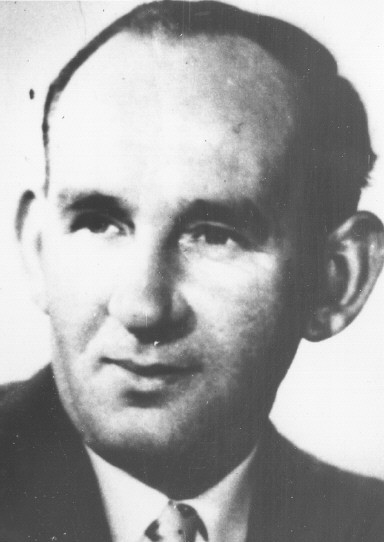

Alexander Pechersky

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Aleksandr Pechersky

Birth name Alexander Aronovich Pechersky

Nickname(s) Sasha

Born 22 February 1909

Kremenchuk, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire

Died 19 January 1990 (aged 80)

Rostov-on-Don, Soviet Union

Allegiance Soviet Union

Service/branch Red Army

Rank Captain

Battles/wars World War II

Awards Medal for Battle Merit (1951), Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945"

Spouse(s) Olga Kotova

Other work Music theater administration

Alexander 'Sasha' Pechersky (Russian: Алекса́ндр Аро́нович Пече́рский; 22 February 1909 – 19 January 1990) was one of the organizers, and the leader of the most successful uprising and mass-escape of Jews from a Nazi extermination camp during World War II; which occurred at the Sobibor extermination camp on 14 October 1943.

In 1948 Pechersky was arrested by the Soviet authorities along with his brother during the countrywide Rootless cosmopolitan campaign against the Jews suspected of pro-Western leanings. Only after Stalin's death in 1953 was he released from jail due in part to mounting international pressure. However, the harassment did not stop there. Pechersky was prevented by the Soviet government from testifying in multiple international trials related to Sobibor, including the Eichmann Trial in Israel. The last time he was refused the permission to exit the country and testify was in 1987, for a trial in Poland.

Biography

Pechersky, a son of a Jewish lawyer, was born on February 22, 1909 in Kremenchuk, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire (now Ukraine). In 1915, his family moved to Rostov-on-Don where he eventually worked as an electrician at a locomotive repair factory. After graduating from university with a diploma in music and literature, he became an accountant and manager of a small school for amateur musicians.

World War II

On 22 June 1941, the day when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Pechersky was conscripted into the Soviet Red Army with a rank of junior lieutenant. By September 1941, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant quartermaster (class II). In the early autumn of 1941, he rescued his wounded commander from being captured by the Germans. He didn't receive any medals for this deed. One of his fellow soldiers reportedly said: "Sasha, if what you've done doesn't make you a hero, I don't know who is!" In October 1941, during the Battle of Moscow, their unit was surrounded and captured by the Germans in the pocket at the city of Vyazma, Smolensk Oblast.

Captured, Pechersky soon contracted typhus, but survived the seven-month-long illness. In May 1942, he escaped along with four other prisoners of war, but they were all recaptured the same day. He was then sent to a penal camp at Borisov, Belarus, and from there to a prisoners of war (POW) camp located in the forest next to the city of Minsk. During a mandatory medical examination it was discovered that he was circumcised. Pechersky recalled a German medical officer asking him: "Do you admit to being a Jew?" He admitted it, since any denial would result in a whipping, and was thrown into a cellar called "the Jewish grave" along with other Jewish POWs (prisoners of war), where for 10 days he sat in complete darkness, being fed 100 grams (3.5 oz) of wheat and a cup of water every second day.

On August 20, 1942, Pechersky was sent to a SS-operated arbeitslager, a work camp, in Minsk. The camp housed 500 Jews from the Minsk Ghetto, as well as Jewish Soviet POWs; there were also between 200–300 Soviet inmates whom the Germans labeled as incorrigible: people who were suspected of contacting the Soviet partisans and those who were repeatedly truant while working for the Germans. The prisoners were starved and worked from dawn till dusk. Pechersky wrote about the Minsk work camp:

The German Nazi camp commandant didn't let a single day pass without killing someone. If you looked at his face you could tell he was a sadist. He was thin, his upper lip shaking and his left eye bloodshot. He always had a hangover or was drunk and committed unspeakable horrors. He shot people for no reason and his favorite hobby was commanding his dog to attack random people who were ordered not to defend themselves. — Pechersky

At Sobibor

On 18 September 1943, Pechersky, along with 2,000 Jews from Minsk including about 100 Soviet Jewish POWs, was placed in a train cattle car which arrived at the Sobibor extermination camp on September 23, 1943. Eighty prisoners from the train, including Pechersky, were selected for work in Lager II. The remaining 1,920 Jews were immediately led to the gas chambers. Pechersky later recalled his thoughts as the train pulled up to Sobibor, "How many circles of hell were there in Dante's Inferno? It seems there were nine. How many have already passed? Being surrounded, being captured, camps in Vyazma, Smolensk, Borisov, Minsk... And finally I am here. What's next?" The appearance of Soviet POWs produced an enormous impression on Sobibor prisoners: "hungry hope-filled eyes following their every move".

Pechersky wrote about his first day in Sobibor:

I was sitting outside on a pile of logs in the evening with Solomon (Shlomo) Leitman, who subsequently became my top commander in the uprising. I asked him about the huge, strange fire burning 500 meters away from us behind some trees and about the unpleasant smell throughout the camp. He warned me that the guards forbade looking there, and told me that they are burning the corpses of my murdered comrades who arrived with me that day. I did not believe him, but he continued: He told me that the camp existed for more than a year and that almost every day a train came with two thousand new victims who are all murdered within a few hours. He said around 500 Jewish prisoners – Polish, French, German, Dutch and Czechoslovak work here and that my transport was the first one to bring Russian Jews. He said that on this tiny plot of land, no more than 10 hectares, (24.7 acres or .1 square kilometer) hundreds of thousands of Jewish women, children and men were murdered. I thought about the future. Should I try to escape alone or with a small group? Should I leave the rest of the prisoners to be tortured and murdered? I rejected this thought. — Pechersky

During his third day at Sobibor, Alexander Pechersky earned the respect of fellow prisoners by standing up to Karl Frenzel, an SS senior officer, as the incident was recalled by Leon Feldhendler.

Pechersky, still wearing his Soviet Army uniform, was assigned to dig up tree stumps in the North Camp. Frenzel was in charge because an underling was elsewhere and was in a bad mood. Frenzel was waiting for an excuse to pick on someone since he considered himself an officer and a gentleman and waited for some reason to begin his sadistic games. One Dutch Jew was too weak to chop a stump so Frenzel began beating him with his whip.

Pechersky stopped chopping and watched the whipping while resting on his axe. Kapo Porzyczki translated when Frenzel asked Pechersky if he didn’t like what he saw. Pechersky didn't bow down, shake or cower in fear but answered, Yes Oberscharfuhrer. Franzel told Pechersky that he had 5 minutes to split a large tree stump in two. If Pechersky beat the time he would receive a pack of cigarettes, if he lost, he would be whipped 25 times. Franzel looked at his watch, and said: Begin.

Pechersky split the stump in four and a half minutes and Frenzel held out a pack of cigarettes and announced that he always does as he promises. Pechersky replied that he doesn’t smoke, turned around and got back to chopping down new tree stumps. Frenzel came back twenty minutes later with fresh bread and butter and offered it to Pechersky. Pechersky replied that the rations at the concentration camp were more than adequate and that he wasn’t hungry. Frenzel turned around and left, leaving Kapo Porzyczki in charge. That evening, this episode of defiance spread throughout Sobibor. This episode influenced the leadership of the Polish Jews to approach Pechersky about ideas for an escape plan. — Leon Feldhendler

Pechersky's plan merged the idea of a mass escape with vengeance: to help as many prisoners as possible to escape while executing SS officers and guards. His final goal was to join up with the partisans and continue fighting the Nazis.

Five days after arriving at Sobibor, Pechersky was again approached by Solomon Leitman on behalf of Leon Feldhendler, the leader of the camp's Polish Jews. Leitman was one of the few prisoners who understood Russian and Pechersky didn't speak either Yiddish or Polish. Pechersky was invited to talk with a group of Jewish prisoner leaders from Poland, to whom he spoke about the Red Army victory in the Battle of Stalingrad and partisan victories. When one of the prisoners asked him why the partisans won't rescue them from Sobibor, Pechersky allegedly replied: "What for? To free us all? The partisans have their hands full already. Nobody will do our job for us."

The Jewish prisoners who had worked at the Bełżec extermination camp were sent to Sobibor to be exterminated when Bełżec closed. From a note found among the clothing of the murdered, the Sobibor prisoners learned that those who had been killed were from work groups in the Belzec camp. The note said: "We worked for a year in Belzec. I don't know where they're taking us now. They say to Germany. In the freight cars there are dining tables. We received bread for three days, and tins and liquor. If all this is a lie, then know that death awaits you too. Don't trust the Germans. Avenge our blood!"

The leadership of the Polish Jews was aware that Belzec and Treblinka had been closed, dismantled and all remaining prisoners had been sent to the gas-chambers and they suspected that Sobibor would be next. There was a great urgency in coming up with a good escape plan, and Pechersky, with his army experience, was their best hope. The escape had to also coincide with the time when the Sobibor's deputy commandant Gustav Wagner went on vacation, since the prisoners felt that he was sharp enough to uncover the escape plan.

Luka

Pechersky clandestinely met with Feldhendler under the guise of meeting Luka, a woman he was supposedly involved with. Luka is often described as an 18-year-old woman from "Holland", but records indicate she was 28 and from Germany, her real name was Gertrud Poppert–Schönborn. After the war, Pechersky insisted that the relationship was platonic. Her fate after the escape was never established and she was never seen alive again. During an interview with Thomas Blatt, Pechersky said the following regarding Luka: "Although I knew her only about two weeks, I will never forget her. I informed her minutes before the escape of the plan. She has given me a shirt. She said, 'it's a good luck shirt, put it on right now', and I did. It's now in the museum. I lost her in the turmoil of the revolt and never saw her again."

Luka's shirt still exists and is described on May 3, 2010 by Pechersky's daughter as:

It is very well preserved. Light gray. Has dark-gray stripes. A little worn from wear and being often washed. Long sleeves. The shirt collar has some blurred letters of the Latin alphabet which are no longer readable.

The uprising

According to Pechersky's plan, the prisoners would assassinate the German SS staff, thereby rendering the auxiliary guards leaderless, obtain weapons, and eliminate the remaining guards. Individual Polish Jewish inmates were assigned specific German SS guards that they were supposed to lure inside the workshops under some pretext and silently kill. Ester Raab, a survivor of the escape, recalled: "The plan was, at 4 o’clock (pm), should start (the escape), everybody has to kill his SS man, and his guard at his place of work." Only a small circle of trusted Polish Jewish inmates were aware of the escape plan as they didn't trust the Jews from other European countries.

On 14 October 1943, Pechersky's escape plan began. During the day, several German SS men were lured to workshops on a variety of pretexts, such as being fitted for new boots or expensive clothes. The SS men were then stabbed to death with carpenters' axes, awls, and chisels discreetly recovered from property left by gassed Jews; with other tradesmen's sharp tools; or with crude knives and axes made in the camp's machine shop. The blood was covered up with sawdust on the floor. The escapees were armed with a number of hand grenades, a rifle, a submachine gun and several pistols that the prisoners stole from the German living quarters, as well as the sidearms captured from the dead SS. Earlier in the day, SS-Oberscharführer Erich Bauer, at the top of the death list created by Pechersky, unexpectedly drove out to Chełm for supplies. The uprising was almost postponed since Bauer's death was felt necessary for the success of the escape. Bauer came back early from Chełm, discovered that SS-Scharführer Rudolf Beckmann had been assassinated, and began shooting at the Jewish prisoners. The sound of the gunfire prompted Alexander Pechersky to begin the revolt earlier than planned. Pechersky screamed the preplanned code-words: "Hurrah, the revolt has begun!"

Disorganized groups of prisoners ran in every direction. Ada Lichtman, a survivor of the escape recalls: "Suddenly we heard shots... Mines started to explode. Riot and confusion prevailed, everything was thundering around. The doors of the workshop were opened, and everyone rushed through... We ran out of the workshop. All around were the bodies of the dead and wounded." Alexander Pechersky was able to successfully escape into the woods. At the end of the uprising, 11 German SS personnel and an unknown number of Ukrainian guards were killed. Out of approximately 550 Jewish prisoners at the Sobibor death camp, 130 chose not to participate in the uprising and remained in the camp; about 80 were killed during the escape either by machine gun fire from watchtowers, or while getting through a mine field in the camp's outer perimeter; 170 more were recaptured by the Nazis during large-scale searches. All who remained in the camp or caught after the escape were executed. However, 53 Sobibor escapees survived the war. Within days after the uprising, the SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered the camp closed, dismantled and planted with trees.

After the escape

Immediately after the escape, in the forest, a group of 50 prisoners followed Pechersky. After some time, Pechersky informed the Polish Jews that he along with a few Soviet Jewish soldiers would enter the nearby village and then shortly return with food. They allegedly collected all the money (Pechersky implies the money collection is a fabricated detail) and weapons except one rifle, but never came back. In 1980, Thomas Blatt asked Pechersky why he abandoned the other survivors. Pechersky answered:

My job was done. You were Polish Jews in your own terrain. I belonged in the Soviet Union and still considered myself a soldier. In my opinion, the chances for survival were better in smaller units. To tell the people straight forward: "we must part" would not have worked. You have seen, they followed every step of mine, we all would perish. what can I say? You were there. We were only people. The basic instincts came into play. It was still a fight for survival. This is the first time I hear about money collection. It was a turmoil, it was difficult to control everything. I admit, I have seen the imbalance in the distribution of the weaponry, but you must understand, they would rather die than to give up their arms. — Pechersky

Pechersky, along with two other escapees, wandered the forests until they ran into Yakov Biskowitz, and another Sobibor escapee. Biskowitz testified at the Eichmann Trial regarding the meeting:

The two of us wandered through the forests, until we met Sasha Pechersky. There were three of them whom I came across. One had weak legs. They wore white clothes made of hand-woven material. They had sunk into mud after escaping. After that, we met together. There were now five of us – we walked to the Skrodnitze forests. There we met the first Jewish partisans called Yehiel's Group (under Yehiel Grynszpan) – it was a group of Jews who had undertaken action. We engaged in sabotaging railway lines, cutting telephone wires, hit-and-run attacks on German army units. — Yakov Biskowitz

The two Russian Jewish soldiers who Yahov Biskowitz met with Pechersky were Alexander Shubayev (who was responsible for executing SS-Untersturmführer Johann Niemann; was later killed fighting the Germans) and Arkady Moishejwicz Wajspapier (who was responsible for executing SS-Oberscharführer Siegfried Graetschus and Volksdeutscher Ivan Klatt; survived the war). For over a year Pechersky fought with the Yehiel's Group partisans as a demolition expert and later with the Soviet group of Voroshilov Partisans, until the Red Army drove out the Germans from Belarus.

As an escaped POW, Pechersky was conscripted into a special penal battalions, conforming to Stalin's Order No. 270 and was sent to the front to fight German forces in some of the toughest engagements of the war. Pechersky's battalion commander, Major Andreev, was so shocked by his description of Sobibor that he permitted Pechersky to go to Moscow and speak to the Commission of Inquiry of the Crimes of Fascist-German Aggressors and their Accomplices. The Commission listened to Pechersky and published the report Uprising in Sobibor based on his testimony. This report was included in the Black Book, one of the first comprehensive compilations about the Holocaust, written by Vasily Grossman and Ilya Ehrenburg.

For fighting the Germans as part of the penal battalions, Pechersky was promoted to the rank of captain and received a medal for bravery. He was eventually discharged after a serious foot injury. In a hospital in Moscow, he was introduced to his future wife, Olga Kotova.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Aleksandr Pechersky

Birth name Alexander Aronovich Pechersky

Nickname(s) Sasha

Born 22 February 1909

Kremenchuk, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire

Died 19 January 1990 (aged 80)

Rostov-on-Don, Soviet Union

Allegiance Soviet Union

Service/branch Red Army

Rank Captain

Battles/wars World War II

Awards Medal for Battle Merit (1951), Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945"

Spouse(s) Olga Kotova

Other work Music theater administration

Alexander 'Sasha' Pechersky (Russian: Алекса́ндр Аро́нович Пече́рский; 22 February 1909 – 19 January 1990) was one of the organizers, and the leader of the most successful uprising and mass-escape of Jews from a Nazi extermination camp during World War II; which occurred at the Sobibor extermination camp on 14 October 1943.

In 1948 Pechersky was arrested by the Soviet authorities along with his brother during the countrywide Rootless cosmopolitan campaign against the Jews suspected of pro-Western leanings. Only after Stalin's death in 1953 was he released from jail due in part to mounting international pressure. However, the harassment did not stop there. Pechersky was prevented by the Soviet government from testifying in multiple international trials related to Sobibor, including the Eichmann Trial in Israel. The last time he was refused the permission to exit the country and testify was in 1987, for a trial in Poland.

Biography

Pechersky, a son of a Jewish lawyer, was born on February 22, 1909 in Kremenchuk, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire (now Ukraine). In 1915, his family moved to Rostov-on-Don where he eventually worked as an electrician at a locomotive repair factory. After graduating from university with a diploma in music and literature, he became an accountant and manager of a small school for amateur musicians.

World War II

On 22 June 1941, the day when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Pechersky was conscripted into the Soviet Red Army with a rank of junior lieutenant. By September 1941, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant quartermaster (class II). In the early autumn of 1941, he rescued his wounded commander from being captured by the Germans. He didn't receive any medals for this deed. One of his fellow soldiers reportedly said: "Sasha, if what you've done doesn't make you a hero, I don't know who is!" In October 1941, during the Battle of Moscow, their unit was surrounded and captured by the Germans in the pocket at the city of Vyazma, Smolensk Oblast.

Captured, Pechersky soon contracted typhus, but survived the seven-month-long illness. In May 1942, he escaped along with four other prisoners of war, but they were all recaptured the same day. He was then sent to a penal camp at Borisov, Belarus, and from there to a prisoners of war (POW) camp located in the forest next to the city of Minsk. During a mandatory medical examination it was discovered that he was circumcised. Pechersky recalled a German medical officer asking him: "Do you admit to being a Jew?" He admitted it, since any denial would result in a whipping, and was thrown into a cellar called "the Jewish grave" along with other Jewish POWs (prisoners of war), where for 10 days he sat in complete darkness, being fed 100 grams (3.5 oz) of wheat and a cup of water every second day.

On August 20, 1942, Pechersky was sent to a SS-operated arbeitslager, a work camp, in Minsk. The camp housed 500 Jews from the Minsk Ghetto, as well as Jewish Soviet POWs; there were also between 200–300 Soviet inmates whom the Germans labeled as incorrigible: people who were suspected of contacting the Soviet partisans and those who were repeatedly truant while working for the Germans. The prisoners were starved and worked from dawn till dusk. Pechersky wrote about the Minsk work camp:

The German Nazi camp commandant didn't let a single day pass without killing someone. If you looked at his face you could tell he was a sadist. He was thin, his upper lip shaking and his left eye bloodshot. He always had a hangover or was drunk and committed unspeakable horrors. He shot people for no reason and his favorite hobby was commanding his dog to attack random people who were ordered not to defend themselves. — Pechersky

At Sobibor

On 18 September 1943, Pechersky, along with 2,000 Jews from Minsk including about 100 Soviet Jewish POWs, was placed in a train cattle car which arrived at the Sobibor extermination camp on September 23, 1943. Eighty prisoners from the train, including Pechersky, were selected for work in Lager II. The remaining 1,920 Jews were immediately led to the gas chambers. Pechersky later recalled his thoughts as the train pulled up to Sobibor, "How many circles of hell were there in Dante's Inferno? It seems there were nine. How many have already passed? Being surrounded, being captured, camps in Vyazma, Smolensk, Borisov, Minsk... And finally I am here. What's next?" The appearance of Soviet POWs produced an enormous impression on Sobibor prisoners: "hungry hope-filled eyes following their every move".

Pechersky wrote about his first day in Sobibor:

I was sitting outside on a pile of logs in the evening with Solomon (Shlomo) Leitman, who subsequently became my top commander in the uprising. I asked him about the huge, strange fire burning 500 meters away from us behind some trees and about the unpleasant smell throughout the camp. He warned me that the guards forbade looking there, and told me that they are burning the corpses of my murdered comrades who arrived with me that day. I did not believe him, but he continued: He told me that the camp existed for more than a year and that almost every day a train came with two thousand new victims who are all murdered within a few hours. He said around 500 Jewish prisoners – Polish, French, German, Dutch and Czechoslovak work here and that my transport was the first one to bring Russian Jews. He said that on this tiny plot of land, no more than 10 hectares, (24.7 acres or .1 square kilometer) hundreds of thousands of Jewish women, children and men were murdered. I thought about the future. Should I try to escape alone or with a small group? Should I leave the rest of the prisoners to be tortured and murdered? I rejected this thought. — Pechersky

During his third day at Sobibor, Alexander Pechersky earned the respect of fellow prisoners by standing up to Karl Frenzel, an SS senior officer, as the incident was recalled by Leon Feldhendler.

Pechersky, still wearing his Soviet Army uniform, was assigned to dig up tree stumps in the North Camp. Frenzel was in charge because an underling was elsewhere and was in a bad mood. Frenzel was waiting for an excuse to pick on someone since he considered himself an officer and a gentleman and waited for some reason to begin his sadistic games. One Dutch Jew was too weak to chop a stump so Frenzel began beating him with his whip.

Pechersky stopped chopping and watched the whipping while resting on his axe. Kapo Porzyczki translated when Frenzel asked Pechersky if he didn’t like what he saw. Pechersky didn't bow down, shake or cower in fear but answered, Yes Oberscharfuhrer. Franzel told Pechersky that he had 5 minutes to split a large tree stump in two. If Pechersky beat the time he would receive a pack of cigarettes, if he lost, he would be whipped 25 times. Franzel looked at his watch, and said: Begin.

Pechersky split the stump in four and a half minutes and Frenzel held out a pack of cigarettes and announced that he always does as he promises. Pechersky replied that he doesn’t smoke, turned around and got back to chopping down new tree stumps. Frenzel came back twenty minutes later with fresh bread and butter and offered it to Pechersky. Pechersky replied that the rations at the concentration camp were more than adequate and that he wasn’t hungry. Frenzel turned around and left, leaving Kapo Porzyczki in charge. That evening, this episode of defiance spread throughout Sobibor. This episode influenced the leadership of the Polish Jews to approach Pechersky about ideas for an escape plan. — Leon Feldhendler

Pechersky's plan merged the idea of a mass escape with vengeance: to help as many prisoners as possible to escape while executing SS officers and guards. His final goal was to join up with the partisans and continue fighting the Nazis.

Five days after arriving at Sobibor, Pechersky was again approached by Solomon Leitman on behalf of Leon Feldhendler, the leader of the camp's Polish Jews. Leitman was one of the few prisoners who understood Russian and Pechersky didn't speak either Yiddish or Polish. Pechersky was invited to talk with a group of Jewish prisoner leaders from Poland, to whom he spoke about the Red Army victory in the Battle of Stalingrad and partisan victories. When one of the prisoners asked him why the partisans won't rescue them from Sobibor, Pechersky allegedly replied: "What for? To free us all? The partisans have their hands full already. Nobody will do our job for us."

The Jewish prisoners who had worked at the Bełżec extermination camp were sent to Sobibor to be exterminated when Bełżec closed. From a note found among the clothing of the murdered, the Sobibor prisoners learned that those who had been killed were from work groups in the Belzec camp. The note said: "We worked for a year in Belzec. I don't know where they're taking us now. They say to Germany. In the freight cars there are dining tables. We received bread for three days, and tins and liquor. If all this is a lie, then know that death awaits you too. Don't trust the Germans. Avenge our blood!"

The leadership of the Polish Jews was aware that Belzec and Treblinka had been closed, dismantled and all remaining prisoners had been sent to the gas-chambers and they suspected that Sobibor would be next. There was a great urgency in coming up with a good escape plan, and Pechersky, with his army experience, was their best hope. The escape had to also coincide with the time when the Sobibor's deputy commandant Gustav Wagner went on vacation, since the prisoners felt that he was sharp enough to uncover the escape plan.

Luka

Pechersky clandestinely met with Feldhendler under the guise of meeting Luka, a woman he was supposedly involved with. Luka is often described as an 18-year-old woman from "Holland", but records indicate she was 28 and from Germany, her real name was Gertrud Poppert–Schönborn. After the war, Pechersky insisted that the relationship was platonic. Her fate after the escape was never established and she was never seen alive again. During an interview with Thomas Blatt, Pechersky said the following regarding Luka: "Although I knew her only about two weeks, I will never forget her. I informed her minutes before the escape of the plan. She has given me a shirt. She said, 'it's a good luck shirt, put it on right now', and I did. It's now in the museum. I lost her in the turmoil of the revolt and never saw her again."

Luka's shirt still exists and is described on May 3, 2010 by Pechersky's daughter as:

It is very well preserved. Light gray. Has dark-gray stripes. A little worn from wear and being often washed. Long sleeves. The shirt collar has some blurred letters of the Latin alphabet which are no longer readable.

The uprising

According to Pechersky's plan, the prisoners would assassinate the German SS staff, thereby rendering the auxiliary guards leaderless, obtain weapons, and eliminate the remaining guards. Individual Polish Jewish inmates were assigned specific German SS guards that they were supposed to lure inside the workshops under some pretext and silently kill. Ester Raab, a survivor of the escape, recalled: "The plan was, at 4 o’clock (pm), should start (the escape), everybody has to kill his SS man, and his guard at his place of work." Only a small circle of trusted Polish Jewish inmates were aware of the escape plan as they didn't trust the Jews from other European countries.

On 14 October 1943, Pechersky's escape plan began. During the day, several German SS men were lured to workshops on a variety of pretexts, such as being fitted for new boots or expensive clothes. The SS men were then stabbed to death with carpenters' axes, awls, and chisels discreetly recovered from property left by gassed Jews; with other tradesmen's sharp tools; or with crude knives and axes made in the camp's machine shop. The blood was covered up with sawdust on the floor. The escapees were armed with a number of hand grenades, a rifle, a submachine gun and several pistols that the prisoners stole from the German living quarters, as well as the sidearms captured from the dead SS. Earlier in the day, SS-Oberscharführer Erich Bauer, at the top of the death list created by Pechersky, unexpectedly drove out to Chełm for supplies. The uprising was almost postponed since Bauer's death was felt necessary for the success of the escape. Bauer came back early from Chełm, discovered that SS-Scharführer Rudolf Beckmann had been assassinated, and began shooting at the Jewish prisoners. The sound of the gunfire prompted Alexander Pechersky to begin the revolt earlier than planned. Pechersky screamed the preplanned code-words: "Hurrah, the revolt has begun!"

Disorganized groups of prisoners ran in every direction. Ada Lichtman, a survivor of the escape recalls: "Suddenly we heard shots... Mines started to explode. Riot and confusion prevailed, everything was thundering around. The doors of the workshop were opened, and everyone rushed through... We ran out of the workshop. All around were the bodies of the dead and wounded." Alexander Pechersky was able to successfully escape into the woods. At the end of the uprising, 11 German SS personnel and an unknown number of Ukrainian guards were killed. Out of approximately 550 Jewish prisoners at the Sobibor death camp, 130 chose not to participate in the uprising and remained in the camp; about 80 were killed during the escape either by machine gun fire from watchtowers, or while getting through a mine field in the camp's outer perimeter; 170 more were recaptured by the Nazis during large-scale searches. All who remained in the camp or caught after the escape were executed. However, 53 Sobibor escapees survived the war. Within days after the uprising, the SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered the camp closed, dismantled and planted with trees.

After the escape

Immediately after the escape, in the forest, a group of 50 prisoners followed Pechersky. After some time, Pechersky informed the Polish Jews that he along with a few Soviet Jewish soldiers would enter the nearby village and then shortly return with food. They allegedly collected all the money (Pechersky implies the money collection is a fabricated detail) and weapons except one rifle, but never came back. In 1980, Thomas Blatt asked Pechersky why he abandoned the other survivors. Pechersky answered:

My job was done. You were Polish Jews in your own terrain. I belonged in the Soviet Union and still considered myself a soldier. In my opinion, the chances for survival were better in smaller units. To tell the people straight forward: "we must part" would not have worked. You have seen, they followed every step of mine, we all would perish. what can I say? You were there. We were only people. The basic instincts came into play. It was still a fight for survival. This is the first time I hear about money collection. It was a turmoil, it was difficult to control everything. I admit, I have seen the imbalance in the distribution of the weaponry, but you must understand, they would rather die than to give up their arms. — Pechersky

Pechersky, along with two other escapees, wandered the forests until they ran into Yakov Biskowitz, and another Sobibor escapee. Biskowitz testified at the Eichmann Trial regarding the meeting:

The two of us wandered through the forests, until we met Sasha Pechersky. There were three of them whom I came across. One had weak legs. They wore white clothes made of hand-woven material. They had sunk into mud after escaping. After that, we met together. There were now five of us – we walked to the Skrodnitze forests. There we met the first Jewish partisans called Yehiel's Group (under Yehiel Grynszpan) – it was a group of Jews who had undertaken action. We engaged in sabotaging railway lines, cutting telephone wires, hit-and-run attacks on German army units. — Yakov Biskowitz

The two Russian Jewish soldiers who Yahov Biskowitz met with Pechersky were Alexander Shubayev (who was responsible for executing SS-Untersturmführer Johann Niemann; was later killed fighting the Germans) and Arkady Moishejwicz Wajspapier (who was responsible for executing SS-Oberscharführer Siegfried Graetschus and Volksdeutscher Ivan Klatt; survived the war). For over a year Pechersky fought with the Yehiel's Group partisans as a demolition expert and later with the Soviet group of Voroshilov Partisans, until the Red Army drove out the Germans from Belarus.

As an escaped POW, Pechersky was conscripted into a special penal battalions, conforming to Stalin's Order No. 270 and was sent to the front to fight German forces in some of the toughest engagements of the war. Pechersky's battalion commander, Major Andreev, was so shocked by his description of Sobibor that he permitted Pechersky to go to Moscow and speak to the Commission of Inquiry of the Crimes of Fascist-German Aggressors and their Accomplices. The Commission listened to Pechersky and published the report Uprising in Sobibor based on his testimony. This report was included in the Black Book, one of the first comprehensive compilations about the Holocaust, written by Vasily Grossman and Ilya Ehrenburg.

For fighting the Germans as part of the penal battalions, Pechersky was promoted to the rank of captain and received a medal for bravery. He was eventually discharged after a serious foot injury. In a hospital in Moscow, he was introduced to his future wife, Olga Kotova.

Last edited by a moderator: